After borrowing someone else's container/harness and also forgetting his glasses before boarding the plane, this skydiver proceeded to do a 90-degree turn straight into the ground. He bounced pretty hard and broke his leg on impact -- he also lost both shoes for those of you wondering 😉.

This jumper decided to do a pretty dynamic, front-riser assisted, 90-degree turn out of a sort-of stall surge at a low altitude. It looks like he didn’t have enough altitude and didn’t try to stab out of it.

He noted that he was borrowing someone else’s harness and forgot to bring his glasses on the jump. Both factors likely played a role in this incident.

This jumper said that HE JUMPED WITHOUT HIS GLASSES. If you need corrective lenses, they should be part of your gear check on the ground. If you get on the plane without them and realize it halfway to altitude, you should fly the plane down. Not being able to see your altimeter, other canopies in the air, or (evidently!) how fast the ground is rushing up at you, puts both you and other jumpers at risk.

If you’re using someone else’s gear, you shouldn’t go straight back into swooping. Take a few jumps to get comfortable with how it flies before returning to your normal routine.

One of the most important things that a lot of canopy coaches do in their courses is getting students familiar with stabbing out to abort a run. It’s a very important skill because a lot of people don’t realize how much harder it is to stab out of a dive when you’ve got some speed built up in a turn. Jumpers need to be ready to give up a run to prevent themselves from slamming into the ground like this guy did.

This skydiver deployed their main canopy and had a bag lock, so they cutaway and deployed their reserve. However, the cutaway didn't fully release and their un-deployed main began trailing behind them. They managed to disconnect it by pulling on the riser, reeled it in (lines flailing and all), held it between their legs and landed with it. Note: this is NOT advisable.

Several factors can contribute to a bag lock: long line stows can lock each other off, a stow can get pulled into a grommet, a pilot chute can be in need of replacement, etc. We would need more information to make a definitive statement about what specifically caused this bag lock.

It’s hard to see what this jumper’s hands were doing once they decided to cutaway. The first thing that comes to mind is that they didn’t pull their handle all the way or that the cables were too long, but it appears like they dropped the handle so that may not be the case. One alternative is that there could have been a mechanical issue like the shackle from their RSL could have jammed their three-ring.

We make this statement more than any other: take packing seriously... Every. Single Time. Don’t rush, go step-by-step and don’t let yourself get distracted or complacent. When it comes to preventing bag locks, a few steps are particularly important: make sure to cock your pilot chute and don’t put too much (no more than 2 inches) excess through your stows; it can help prevent the stows from potentially catching each other.

Skydiving gear is not cheap so the instinct to reel in a main during an incident like this is understandable. However, it’s not the safest option for a few reasons. First, it distracts you from focusing on a safe landing and – especially if you’re landing off already – that needs to be your top priority. Next, all those lines flying around could have easily wrapped around this jumper’s hands, risers, etc., and escalated this situation into something even scarier. Last, as one individual who viewed this video noted, the main was creepy close to coming out of the bag as this jumper reeled it in. Had it deployed it could also have potentially made this situation worse.

Fortunately, this jumper was able to fully release this incomplete cutaway with nothing but a tug on the riser. Had that not worked and the main actually deployed, they may have been in a position where they would want to cut that riser. We don’t know if they had a hook knife, but this could have easily become a situation which warranted one. (So, as we’ve asked before, is your hook knife part of your gear checks?)

This jump very nearly turned catastrophic when one tandem instructor (TI) deployed seconds before impacting another tandem that was already under canopy. Tandem sandwiches are not particularly tasty so we’re glad that the second TI didn’t pitch any later.

There are a bunch of possible issues, or combinations thereof, that could’ve contributed to this incident.

The second group may have not waited long enough in the door. This occasionally happens with the last tandems getting out of the plane if a TI is concerned about getting back to the dropzone (DZ). One TI who viewed this clip noted that, given how much time it takes for a videographer to get settled in and for a TI to get set up in the door, they don’t believe this to be as likely.

This jump lasts about 50 seconds from exit to deployment. If they exited at 10,000 feet instead of 13,500 feet – common at many dropzones – they could have been low.

The first group may have deployed early. This also sometimes happens when TI’s are concerned about making it back to the DZ after exiting close to the end of jump run.

Sometimes a TI – or any jumper – will deploy and then take a second to get settled in without realizing that they are flying up jump run.

Some dropzones and/or pilots pressure their TI’s to never do a go-around because it costs fuel and throws off the rhythm of operations. Instructors need to know when it’s no longer safe for them to get out. We should never forgo safety in an effort to keep everyone happy. But if your DZO is pushing you to do so, remind them that the lost revenue associated with negative press related to a major incident is going to be a hell of a lot more costly than a few extra dollars of Jet-A.

On every jump it’s important that jumpers remain aware of surroundings in terms of factors like altitude, jump run, the locations of other jumpers, etc. That jump run factor is one that many jumpers fail to consider, once you're open you should make sure you're not drifting towards groups that are exiting after you.

There’s no way to tell if this was an issue during this jump but it happens a lot so we thought we should discuss it. Some fun jumpers think tandems, because they fly huge canopies and deploy higher, can get back from any spot. As a result, they don’t take tandems into consideration when they’re setting up in the door. This can put pressure on TI’s to make unsafe decisions.

If you’re among the first jumpers getting out of the plane, start checking your spot once the door is open on the red light and exit promptly on the green light because if there’s a bunch of people behind you, delays will tend to snowball and grow with each group.

Some belly jumpers (sorry, but it’s a fair stereotype) wait until they’re directly over the landing area in the perfect spot rather than getting out on the green. On a normal day with low winds, approximately one third of the jump should get out before the DZ, one third should get out over the DZ, and one third should get out after the DZ so that there’s an even distribution of canopies spread across the area and everyone can get back. When the first group decides to get out immediately over the landing area instead of prior to it, that can put the final third – typically the tandems – in a precarious spot. Be considerate of your fellow jumpers and get the @#$% out! 😊

As they exited the plane this jumper’s deployment bag came out of their container and gave them a horseshoe malfunction. They realized their pilot chute was still in the BOC and deployed it in an attempt to remedy the situation. Unfortunately, the pilot chute failed to extract the main, resulting in a SECOND malfunction! This time the jumper was faced with a bag lock. They cutaway their main, regained stability and deployed their reserve.

This malfunction occurred because the jumper exited the aircraft in a manner which scraped the back of their container across the side of the aircraft. This may have dislodged the pin, or it could have exposed bridle which then caught air and dislodged the pin. Either way, the deployment bag left the container with the pilot chute still inside the BOC.

In this scenario, the bag lock was almost certainly the result of the horseshoe. When the jumper deployed their pilot chute it got caught up in their lines and almost certainly prevented the bridle from being able to extract the main.

The easiest way for this jumper to have prevented this malfunction would have been for them to make sure to rotate their container away from the side of the plane when exiting the aircraft. Sometimes jumpers are rushing to get out and they forget this basic rule!

This bag lock was likely due to the horseshoe. So, preventing the horseshoe would have probably prevented the bag lock! It should be noted, however, that bag locks occur for many other reasons. Line stows that were left too long can lock one another off, a stow can get pulled into a grommet, a pilot chute can be in need of replacement, etc. A majority of bag locks can be easily prevented. Proper packing is the first step: ensure your line stows are the proper length, double-stow your rubber bands, don't leave too much excess, etc. Additionally, ensuring that your gear is in good working order plays a role because a worn-out pilot chute may not have enough drag to provide for the proper extraction of a main.

In this video the jumper did not have an RSL or a Skyhook and, after cutting away, took a significant delay before pulling their reserve handle. In this case the individual had plenty of altitude to enjoy a short belly jump. However, there have been incidents where a jumper took the time to get stable in an attempt to ensure a clean reserve deployment and their delay resulted in serious injuries and death because they didn’t realize how low they were. Typically, if you’re going to cutaway you should go to your reserve immediately.

On their 10th wingsuit jump, this jumper pitched at approximately 4,000 feet but their pilot chute caught in their burble and did not extract their main. They twisted their body to allow air to catch the PC and wound up in line twists which they fought until around 1,600 feet. After some struggling, they were able to clear the malfunction and land safely.

The jumper described their deployment as a “half-assed throw” of the pilot chute. It’s important for all jumpers to perform a strong deployment to ensure that their PC clears their body and their burble, but it’s even more critical for wingsuiters. As noted in the USPA SIM, “Wingsuits create a large burble above and to the back of a skydiver, and may not provide the pilot chute enough air for a clean inflation and extraction of the deployment bag from the pack tray.”

In the details provided with this video submission, the wingsuit pilot noted that he was new to the discipline and did not have an extended bridle. He was flying good equipment for a beginner (an Electra 170 canopy and a Piranha3 wingsuit) but didn’t consider how his bridle – which he had probably been using for regular jumps – would perform behind a wingsuit.

A LOT of jumpers get lazy about their deployment procedures and just go through the motions. Many get in the mindset that, because freefall is over, the jump is over. However, a skydive isn’t complete until you’re back on the ground. While freefall is what appeals most to many jumpers, the deployment and canopy flight are parts of the jump that still require contemplation and attention.

Different disciplines require different equipment considerations. Freeflyers, for example, place emphasis on their deployment systems and operation handles because premature openings at freefly speeds are dangerous. Wingsuit jumps have their own requirement. The USPA SIM notes that wingsuiters should not use a pilot chute smaller than 24 inches, that their pilot chute handles should be as light as possible, and that “bridle length should be increased as the wingsuiter moves into larger suits that create larger burbles.” This jumper may have not been at the point where they thought bridle length needed to be a consideration but, had they been using an extended bridle, this incident may have not occurred.

Ask ten jumpers how to deal with line twists and you'll likely get twelve answers. This individual chose to use the pull-apart method. Others may say he should have brought the risers together to get the twists further down the lines. Debating this issue is a time honored skydiver tradition and we're not going to get into it (again). We did, however, want to mention the importance of maintaining altitude awareness while in line twists. While fighting line twists, many skydivers completely lose track of how high they are and some have cut away dangerously low. This jumper stayed calm, checked his altimeter, and made a conscious decision about whether he thought he had enough altitude to continue fighting or if he had reached his decision altitude for a cutaway. Good job!

Two jumpers were coming in for a landing on a day where there was some congestion in the pattern. The first skydiver – flying a yellow canopy – initiated a front riser assisted 90-degree turn. As they completed their turn the second jumper – under the green canopy – flew into them. The first jumper was spun around 180 degrees and had a few lines rip off at the connection points. Fortunately, their canopy stayed pressurized and they landed down wind without injury. The second jumper suffered some superficial burns from either the lines or the nose of the yellow canopy.

At one point it is clear that four jumpers are all on final at the same time. When there are multiple people trying to land at the same time there is an increased chance of a mid-air collision.

The second jumper stated that he thought the yellow canopy was further away than it was. However – especially on a day where there is a lot of traffic – the pilot of the green canopy should have never allowed that to have become a factor.

On days where there is a lot of canopy traffic, jumpers should be particularly aware of ensuring that they are giving each other plenty of space. They should be cognizant of where everyone else is, should know the differences in wing loading between themselves and other jumpers on the load, and should create space.

We try our best to create proper horizontal and vertical separation between groups when exiting the plane and at break-off, but once we’re under canopy there are choices we make that can either increase or decrease the separation we’ve created for safety during the skydive. If we all try to land in the same spot, or land close to the hangar because we don’t want to walk far, or spiral to get down faster, or don’t want to get our feet wet in the puddles or pond, then you might find yourself in a situation like this. There’s LOTS of space in the sky and in the landing area (usually), so use it to your advantage for safe landings.

Some jumpers get so focused on completing the turn that they are planning on being the first one down that they forsake safety. In a situation where there are a lot of canopies in the air, a boring, standard and safe pattern should be the default option.

This jumper was coming in for a planned 180-degree swoop and initiated the turn way too low, but they failed to recognize their mistake quickly enough and didn't attempt to abort. The end result was a pretty hard impact and a bounce; there was no mention of the injuries, but they noted: “although it’ll take some time to recover, it’s looking very promising that (they) will be back in the sky soon enough.”

This jumper flew a smooth pattern and did a good job checking their air space, but when they began their turn, it quickly becomes evident that they do not have enough altitude. However, at no point do they appear to really abort. This suggests they may have lacked the necessary situational awareness or level of experience for swooping.

Generally speaking, most canopy pilots believe a 180-degree turn is a poor choice. It’s a blind turn that cannot be initiated from base leg so the jumper loses sight picture of the landing area. Comparatively, with a 90- or 270-degree turn, a jumper is on base leg, perpendicular to their landing area and can see where they are going.

A canopy pilot we consulted in this analysis unequivocally said they do not know of a coach who teaches a 180-degree turn. This suggests the jumper may have been learning on their own or getting advice from people who were not qualified to offer it. Most of the best canopy pilots in the world still continuously reach out for coaching and advice so, suffice it to say, someone doing a beginner turn should be reaching out to qualified individuals as well.

Some budding canopy pilots forget that you can land without swooping! (Seriously, it’s totally doable 😉) They will initiate a turn, realize they’re in a questionable position, and still decide to follow through on their planned swoop. If/when you realize that you have put yourself into a dangerously low turn, a jumper should be prepared to stab out on toggles. One of the first drills some canopy coaches teach for "intro to swooping" courses is having a student do a turn at altitude and then stab out of it just so that they become familiar with what it feels like to bail out on toggles.

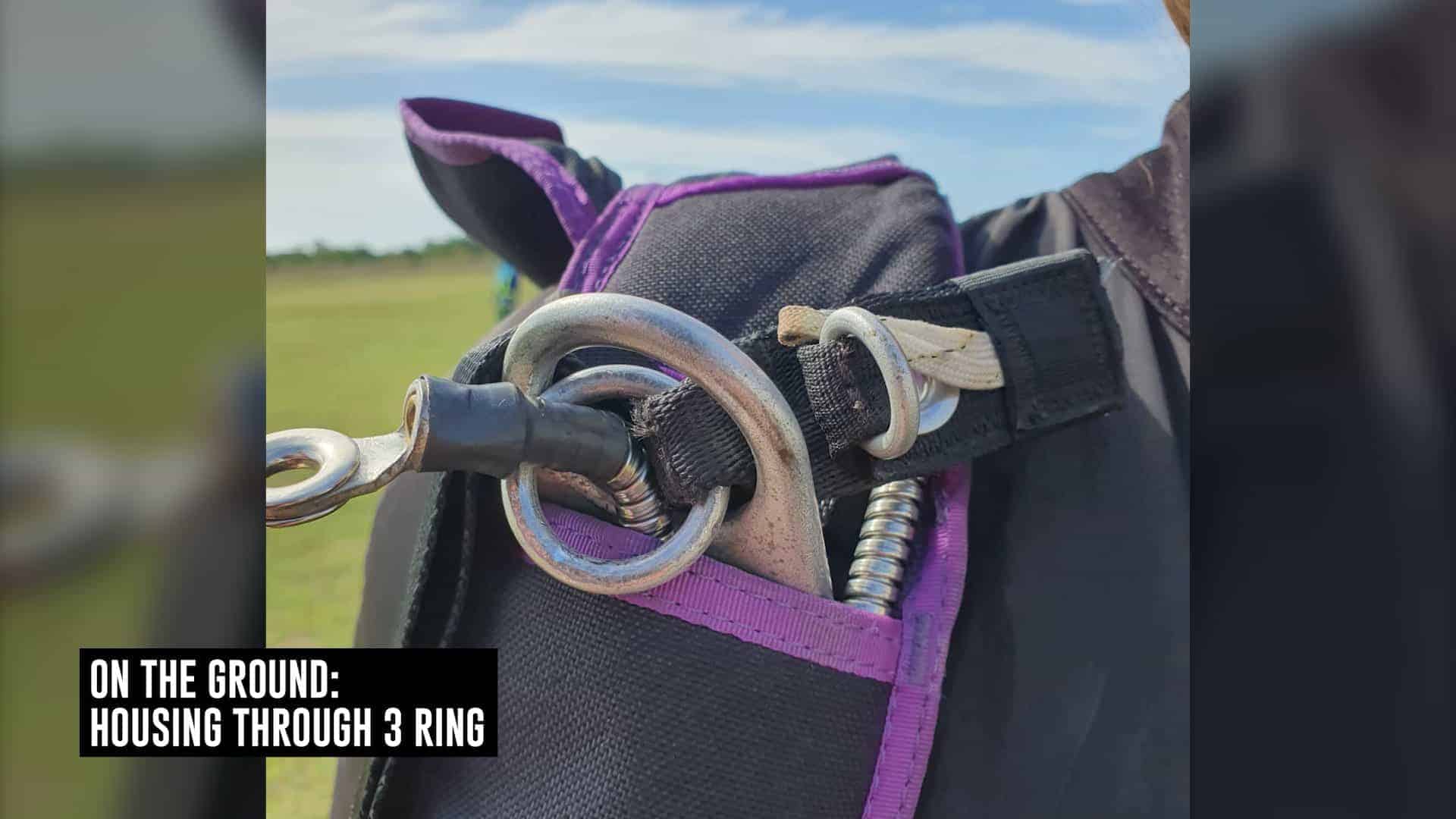

This crazy incident started off with a bag lock malfunction that quickly turned into a one-in-a-million freak accident -- the hard housing passed through the 3-ring assembly -- which had to be cut way with a hook knife to avoid an entanglement with her reserve.

We can’t see the initial malfunction, but the jumper said it was a bag lock. Bag locks occur for a wide variety of reasons, but most are related to improper packing procedures. Often the mistake is putting too much excess line through a stow and creating a large "bite" that can then catch and lock onto a neighboring bite on the d-bag during the deployment process.

It appears that in, what can only be described as a freak accident, this jumper’s hard housing passed through the second ring on her 3-ring-assembly and prevented a clean cutaway of her main parachute. Her rig was inspected, and it was confirmed that her container was properly assembled. One rigger we consulted believes that the exposed hard housing was possibly whipping around and could have passed through the second ring before the reserve deployment created enough pull to cause the cutaway to occur.

Diligent packing is the key here. When packing a parachute, skydivers should make sure they’re doing it slowly, taking each step one at a time, and not rushing. Complacency often occurs even with the most experienced jumpers because they’re chatting with one another during a pack job or rushing to make a call. Jumpers should make sure to not put too much excess lines through their stows; no more than 2 inches, which can help prevent the stows from potentially catching on one another. One instructor who viewed this video also noted that forgetting to cock a pilot chute could have potentially caused this incident; the main could have left the container but, without the snatch force from a pilot chute to pull through a tight stow, it could have stayed in the deployment bag until the jolt from the reserve opening finally started the deployment.

As noted earlier, this appears to have been a one-in-a-million event that can only be written off to divine intervention. Some incidents cannot be prevented but, fortunately, this jumper was heads-up enough to recognize what she needed to do.

A DZM I know once argued that hook knives should be a mandatory piece of equipment included in gear checks. This video is the perfect example of just how important a hook knife can be to saving your life. Notably, the jumper in this video said she only started carrying a hook knife a week before this incident and never thought she would need to use it. We’re really happy she did.

We also wanted to note that this jumper does an excellent job preventing these two canopies from entangling. She knew that the spinning main canopy posed a risk and did a good job keeping it away from her reserve while she got out her hook knife for the (literal) cut away.

During a belly jump with an unknown number of people, one jumper – who made it into the formation – went to pull after not tracking. Another individual – who went low and also didn’t track – deployed while underneath the rest of the group. The first jumper fell through the second jumper’s canopy, blowing out a few cells and requiring a cutaway.

Both jumpers did a poor job tracking. The first jumper – the one who made it into the formation – watched everyone else leave the formation and appears to not move at all. The second jumper – the one who went low – spun a few times but never seems to realize that he needs to track away from the jumpers above him.

The second jumper wasn’t able to stay with the group on a relatively basic belly jump. Staying on level is a skill every jumper should have before joining larger groups.

The skill levels exhibited by both these individuals suggests that this jump was too large. More knowledgeable jumpers should have broken the jump into smaller groups. By placing multiple inexperienced skydivers onto a single jump, the potential for a dangerous situation was increased significantly.

Both of the major issues with this jump – poor tracking and inadequate level control – are skills that a jumper should be relatively familiar with prior to getting their license and, certainly, before attempting larger group jumps. If a jumper is unable to grasp these concepts, they should continue getting coaching before getting cleared to do group jumps.